Today in Nature Astronomy, we published the results of one of our neutrino follow-up campaigns with the Zwicky Transient Facility.

In that campaign, we managed to identify the Tidal Disruption Event (TDE) AT2019dsg as the probable source of high-energy neutrino IC191001A. The object had first been discovered by ZTF in April 2019, one of 17 identified by a systematic search for TDEs with ZTF. The neutrino itself was detected by IceCube several months later, on 1st October 2019. Within seven hours, we had observed the neutrino localisation with ZTF, and quickly realised that AT2019dsg was an exciting object.

TDEs are rare objects, but AT2019dsg was also particularly bright. Accounting for all 8 neutrino follow-up campaigns completed to March 2020, the probability of finding such a bright TDE coincident with a neutrino is just 0.2%.

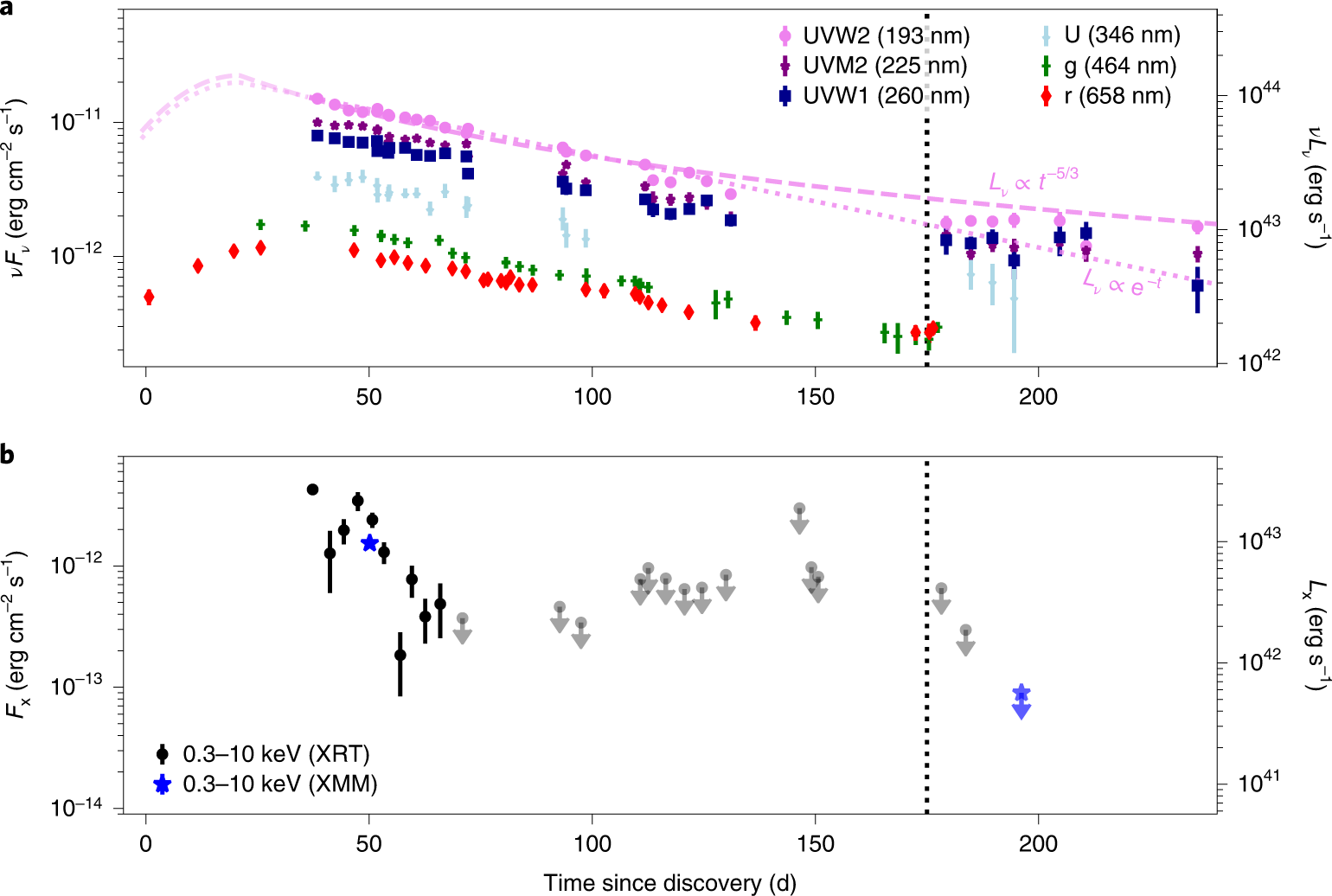

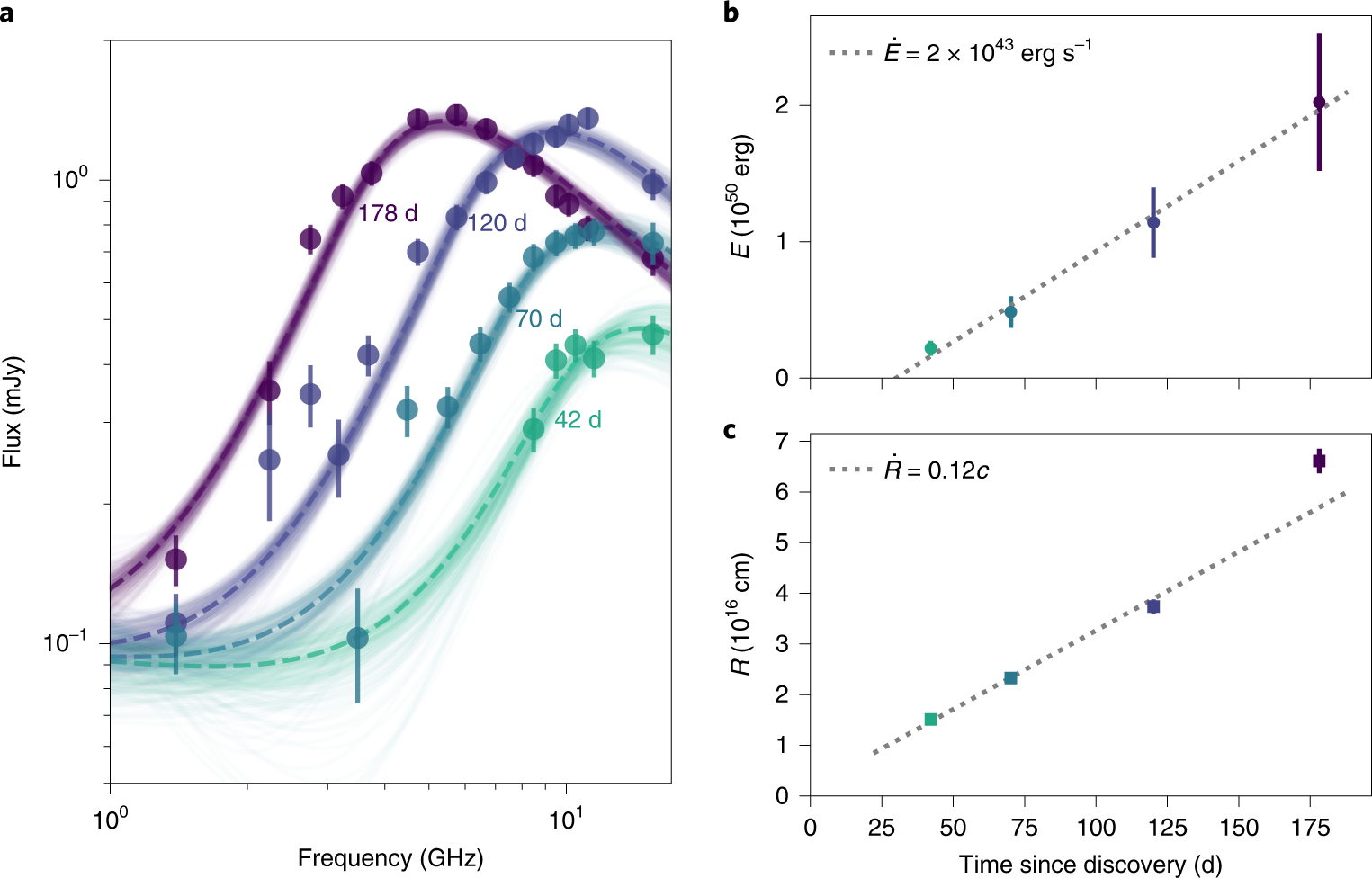

One initial surprise about the association was the long delay between optical peak and neutrino detection. However, having identified AT2019dsg, we immediately triggered a broad multi-wavelength follow-up campaign with many different telescopes. The radio data we obtained (shown below) was crucial to unravelling the mystery. Being detected at all in radio already confirmed that AT2019dsg was acting as a cosmic particle accelerator, an important prerequisite for neutrino production. But analysis of that data, shown below, confirmed that the TDE had a central engine which steadily powered particle acceleration through to the time of the neutrino detection. Since neutrinos can be detected at any time while particle acceleration is occurring, there’s nothing strange about the delay in hindsight.

This is only the second time a probable high-energy neutrino source has been identified, and provides the first observational evidence supporting the long-standing predictions that TDEs could serve as neutrino sources.

You can also view the published version without a Nature Subscription here, along with an accompanying blogpost.